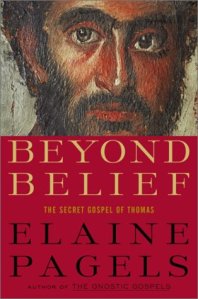

Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas

Elaine Pagels

Death and sadness. Can you think of two better reasons people seek solace in religion?

Death and sadness. Can you think of two better reasons people seek solace in religion?

Maybe you can. I am not here to proselytize. I feel compelled to note, though, that non-belief is also a belief system and that, religion being an almost universal human development, you cut yourself off from a big chunk of humanity when you dismiss the subject.

But let’s get back to the nouns I started with. I never wanted to know too much about writers of fiction because I feared blurring the line between author and character. But in non-fiction and scholarly work a little biography can explain a whole lot (including bias).

Elaine Pagels must believe the same thing because she discloses quite a bit upfront in this volume. The book opens with Pagels entering a church soon after receiving a diagnosis of the disease that will ultimately take her child’s life. Heart-wrenching and a very non-scholarly way of starting what’s going to be more scholarly than a lot of books shelved in the religion section.

This isn’t some post-modernist hugfest, though, and Pagels actually displays quite a bit of autobiographical reticence. I first read her in the early 1980s, soon after The Gnostic Gospels first appeared in paperback, and I’ve tried to keep up since. So I’m well aware that in addition to the loss of a child she also endured the death of her husband, the physicist Heinz Pagels, in a mountaineering accident. I am drawn to sadness and, my Lord, Pagels has certainly been dealt her share.

Here she uses the comfort she found in a congregation as a springboard into the Gospel of Thomas. For those who need a brush up on their Gospels, Thomas is not one of the four gospel authors collected in the New Testament. Those four are referred to as the Canonical gospels. And of the four, three are known as the synoptic gospels while the last is known as, well, the Gospel According to John or, sometimes, as just the Fourth Gospel. If it isn’t already clear, Thomas is not among these. His gospel probably belongs among the Apocrypha or maybe even the more rarefied subset of the Gnostic Gospels.

If that last paragraph gave you a headache this may not be the book for you. If you’re looking for a translation of a ‘missing’ Gospel this isn’t the book for you. If you’re looking for your belief system–and I cast that net broadly to encompass the swath between fundamentalism and atheism– ratified, this is definitely not the book for you. If you have any interest in Church history or religion as a social phenomenon, well, I invite you to dive in.

The Church Fathers, an 11th-century Kievan miniature from Svyatoslav’s Miscellany. As found on Wikipedia.

Pagels has been identified (most notably here, on the Wikipedia page for Heinz Pagels ) as a theologian. I don’t think that’s correct. Theology is a branch of philosophy that works out the doctrinal issues of different religions. It’s raw material is scripture and the writings of other theologians. In the tradition in which I was raised a theologian is further defined as someone whose writing is sanctioned by imprimatur. Things are no doubt looser in traditions less wedded to a hierarchical structure.

Pagels, a historian of the early church, by necessity works with the same source materials: scripture, both canonical and non-canonical, and the writings of the Church Fathers. I see how the mistake can be made, but it’s a bit of a doozy.

Here Pagels takes on one of the non-canonical Gospels and illustrates the role it played in early Church history. The book’s title and subtitle are somewhat misleading because this book really dwells on how scriptures were used by players in the nascent Church to advance agendas. At this remove, almost two millenia after Christ’s life and death and approaching the 500th anniversary of The Ninety-Five Theses, it’s hard to remember that for several hundred years the Church was threatened by secular power and often held outlaw status.

Read enough of these non-canonical works and you may find your head spinning. Because at the end of the day the story they tell is, in broad outline, the same. So you might find yourself wondering: Why not throw them all in the blender (or the Bible) and let the reader figure it out?

The author of Thomas might agree with that approach since its principal difference with the canonical works is that it allows for the possibility of on-going revelation. The history of the early Church is, in large part, the tale of working out just what beliefs constitute the Christian religion and such seemingly mundane things were huge to the participants. Evidently none loomed larger than whether revelation had ended soon after Jesus’ death and resurrection or was ongoing.

(Nota bene: Ongoing revelation still presents a theological conundrum and, in fact, the Church of Latter Day Saints incorporates it into its theology. For one man’s modern take on how this can cause trouble, see Jon Krakeur‘s Under the Banner of Heaven.)

Saint Irenaeus

Bishop of Lyons

130-202

One of those early Church Fathers made the eradication of ongoing revelation his personal mission. Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon, largely succeeded. And he did so in part by casting Thomas, and some other works, as heretical because they insisted on the persistence of revelation. The big winner in all of this was The Gospel of John which became the gospel that rounded out the other three with its message of love.

One has to savor the irony that Irenaeus, one of the more skilled and winning bureaucratic fighters in history, is the reason we have that Fourth Gospel in the canon. But Irenaues was committed to his congregants and truly believed in the power of the believing community–that source of comfort and solace Pagels found herself seeking at her lowest moment.

I’m not doing any of this justice, least of all the scholarship. Pagels excels, in these volumes meant for a broader readership than expert scholars, in making arcane subject matter clear and digestible. Every time I read her I learn more and think a bit differently.

And isn’t that the preferred outcome of encountering scholarship?

An absolutely fantastic essay, Tim, that makes me want to dive right in. Nicely done!

Pingback: Poor Wayfaring Strangers | An Honest Con